Creek Week is coming March 13 through 20. During that week Durham is focusing attention on how individual citizens and property owners can with modest efforts deliver significant benefits to the quality of water moving downstream, especially to Jordan Lake.

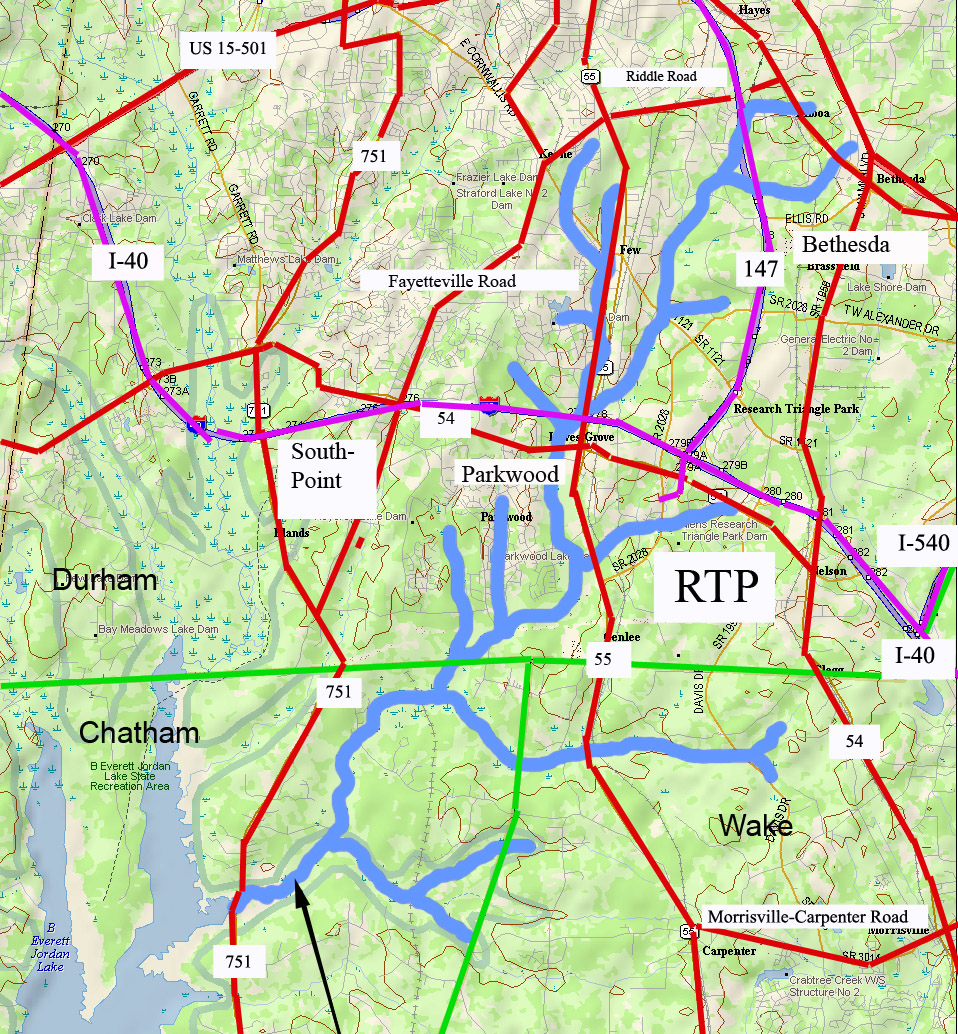

A fun activity during Creek Week is to find the path that water from your roof, sidewalk, driveway, and patio or deck takes as it goes to Northeast Creek, down Northeast Creek and into Jordan Lake, and down the Cape Fear River to Wilmington.

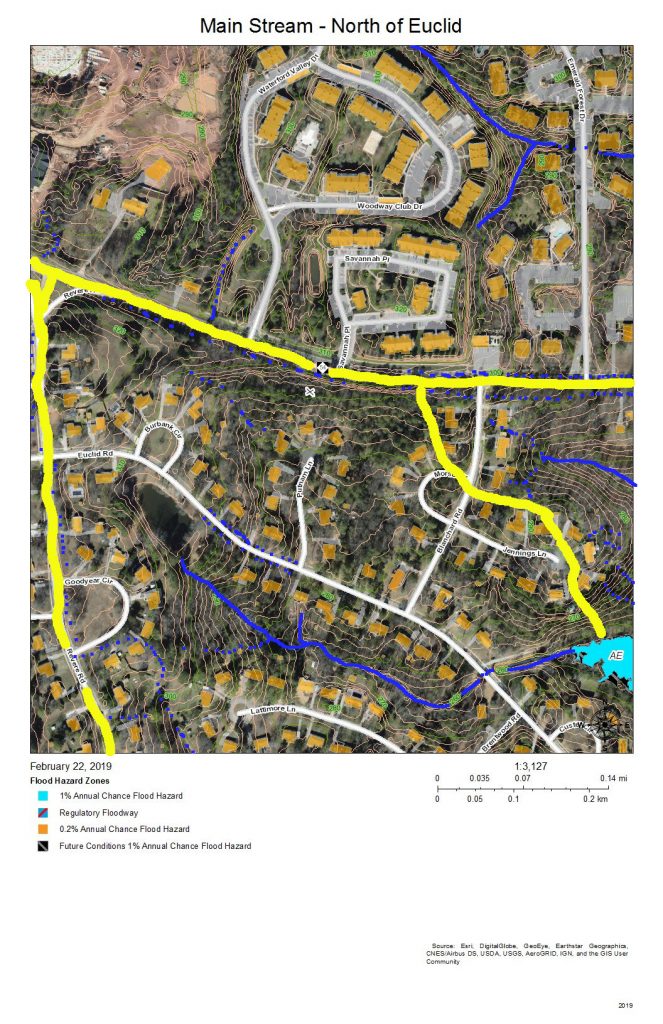

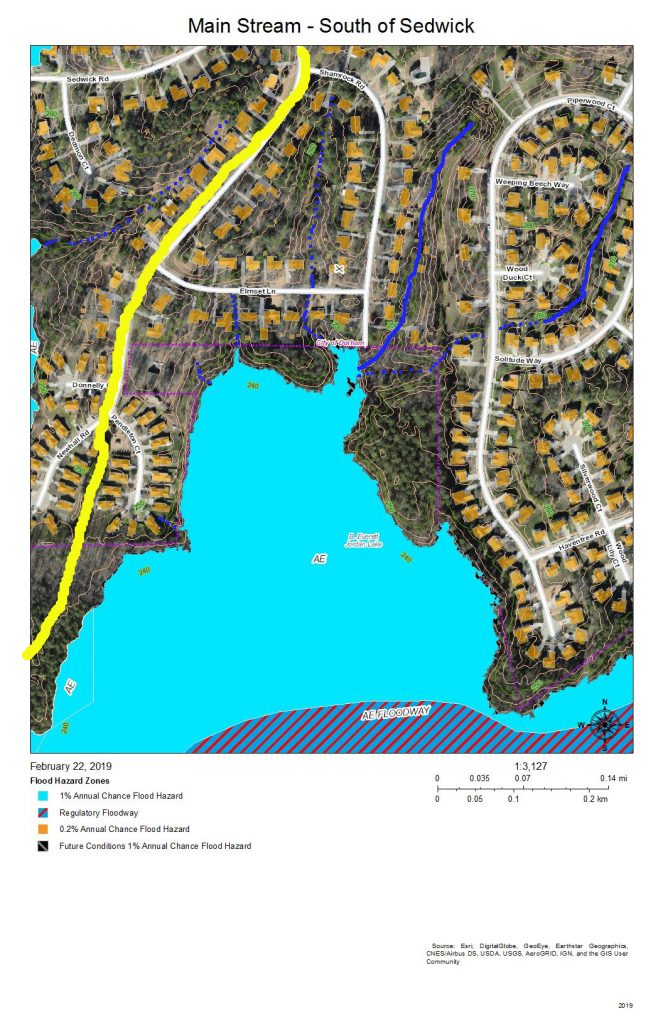

To do that, we must perceive streams and their tributary flows of runoff (the water) in the foreground and land in the background. Focusing on the flash flood zones at full flood (the flood zones identified on the maps) shows the land as necks extending into the fully flooded lake headwaters. After all, one of the primary purposes of Lake Jordan was mitigation of the flash flooding that often occurred in the Haw River and New Hope Creek basins.

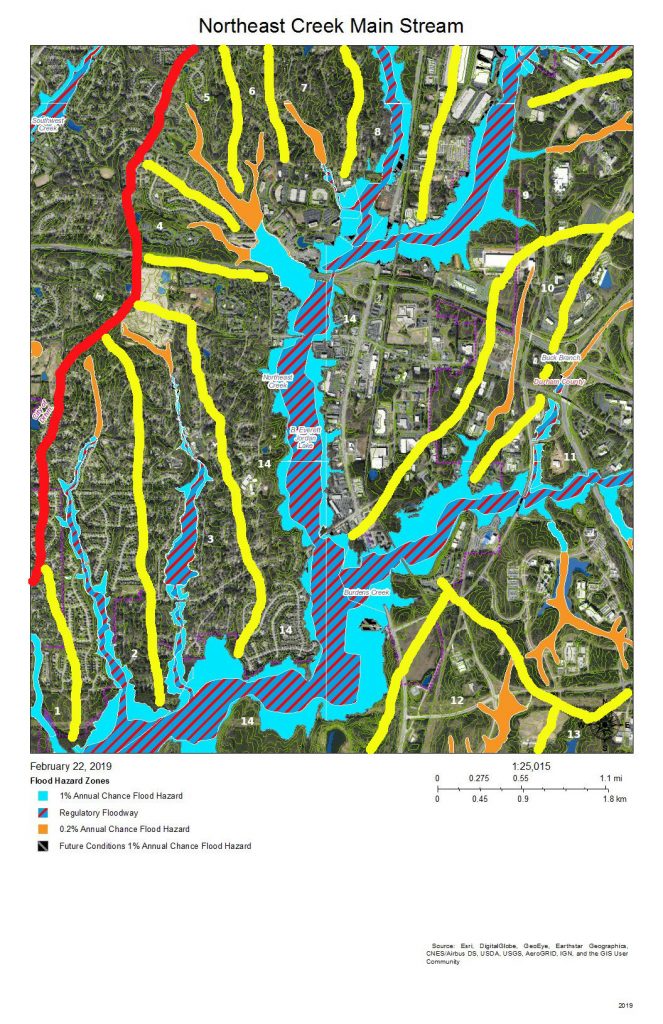

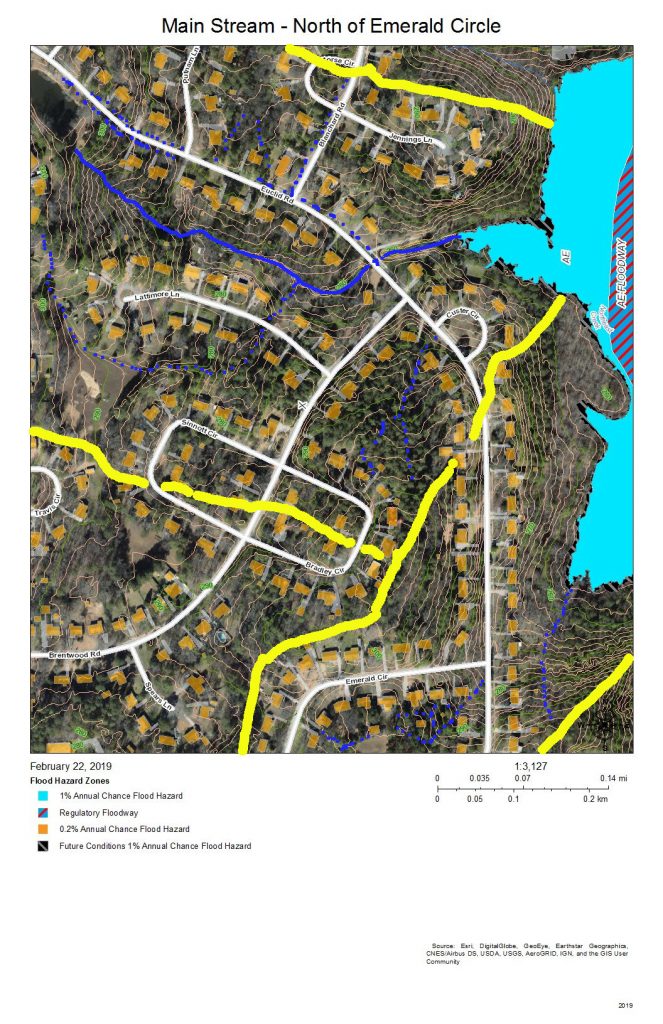

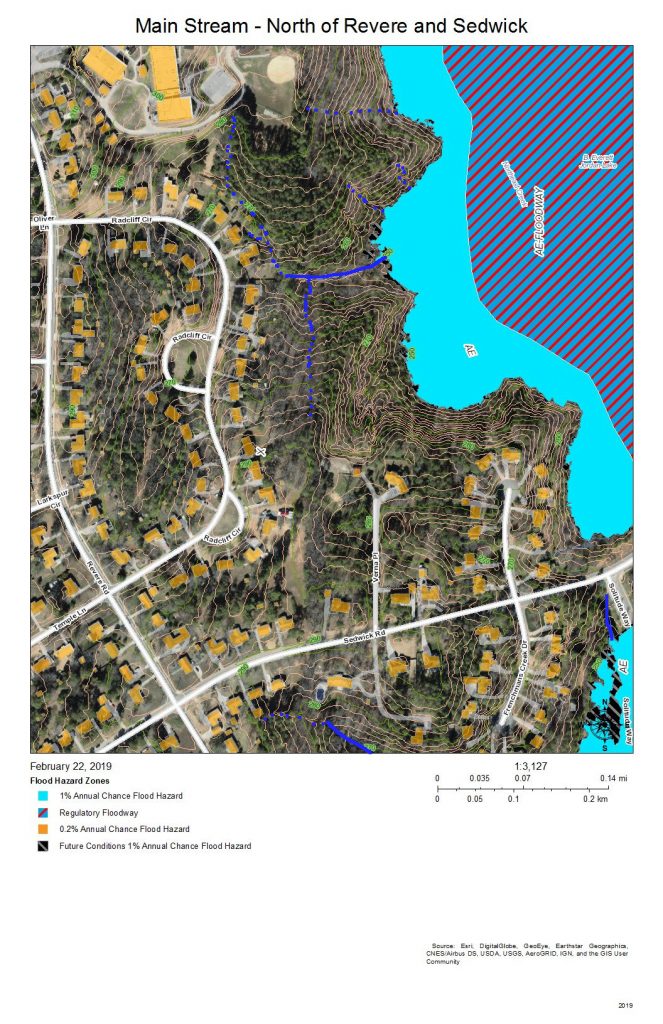

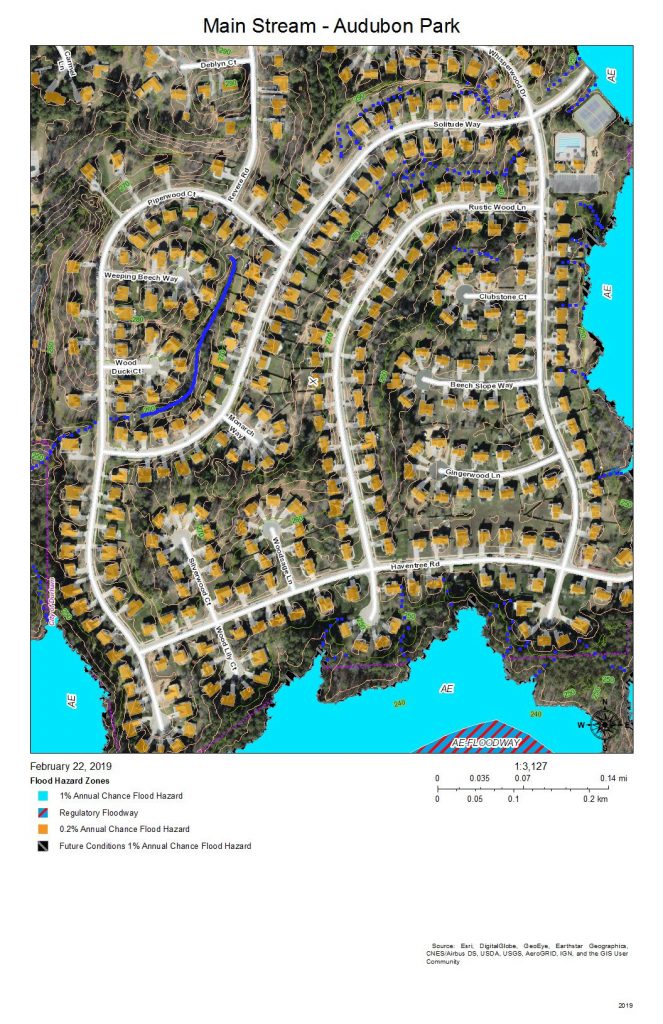

The coloring of the flood zones represent the following:

- Solid blue: 1% annual chance flood hazard

- Blue with red diagonal stripes: Regulatory floodway

- Gold: 0.2% annual chance flood hazard

- Black with gray diagonal stripes: Future conditions 1% annual chance flood hazard.

A second fun activity is to explore the wetlands on US Army Corps of Engineer land set aside for the headwaters of Jordan Lake. The wetlands in these areas comprise:

- periodic flood plains that flood with every rain and become dry land with every dry spell;

- freshwater marshes;

- periodic swamp forests;

- persistent swamp forests that give way to snags (dead trees that host animals like woodpeckers) then become pools of blow-downs (blown-over dead trees);

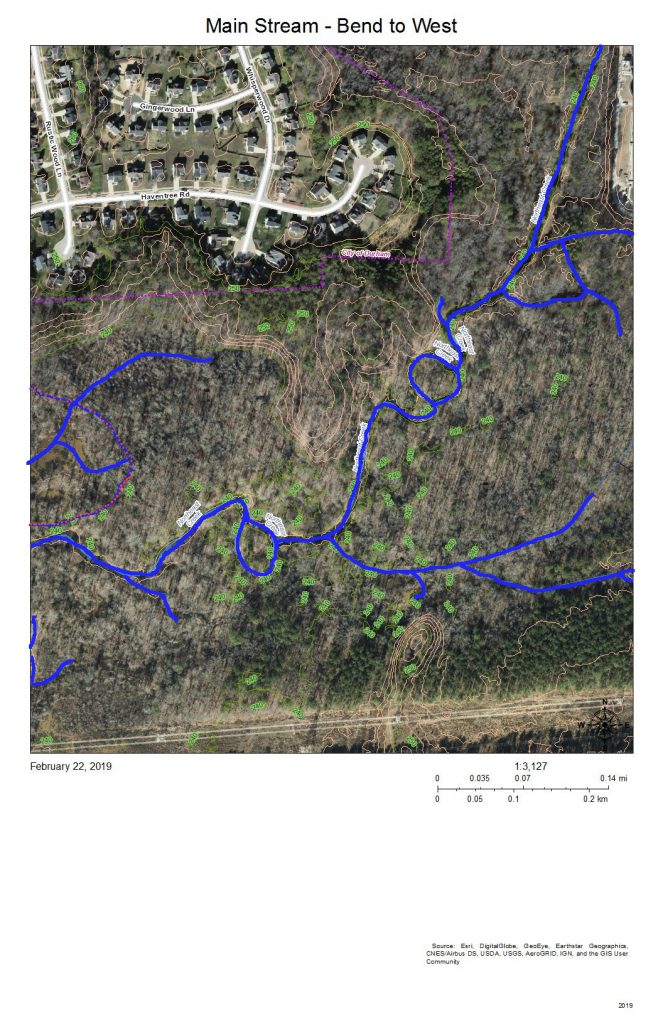

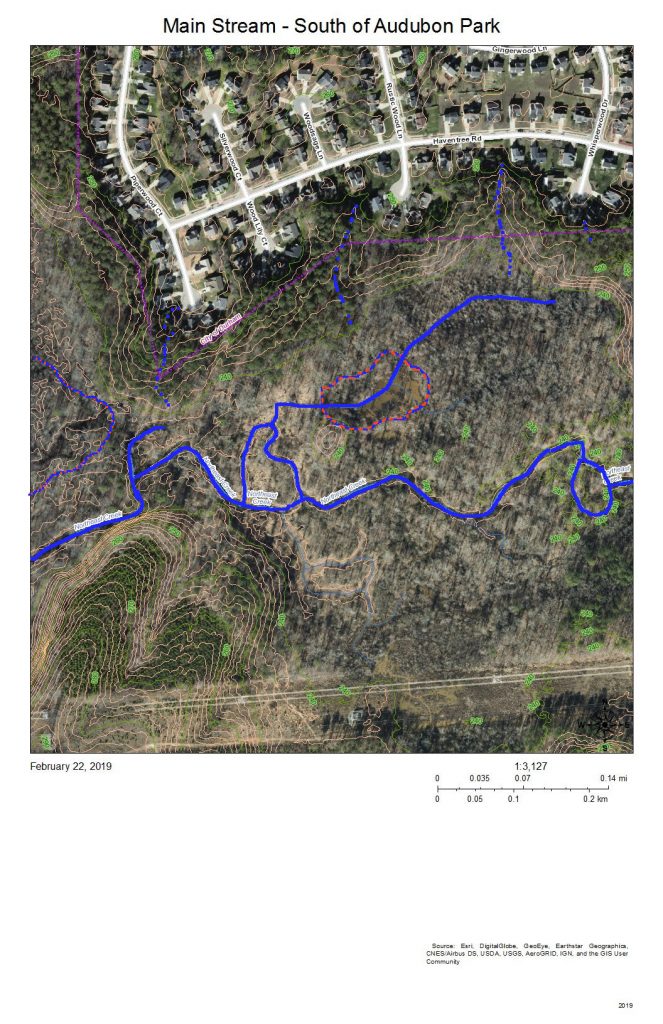

- tightly meandering stretches of stream;

- braided streams;

- oxbow ponds.

These organize themselves to best handle the flow of water through the wetlands in wet and dry periods.

On the maps, wetland features are marked with dotted blue and orange lines.

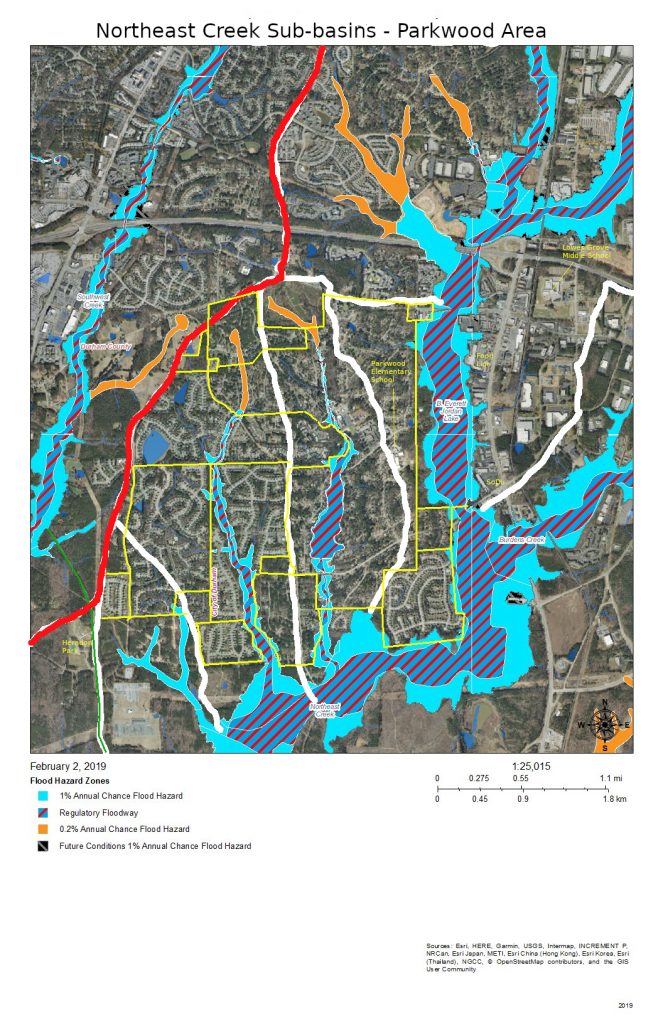

A previous post showed that Parkwood comprises parts of three sub-basins:

- The main stream of Northeast Creek on the east;

- Tributary C feeding Parkwood Lake in the center;

- Tributary D draining the western part of the McCormick high land and streams from Hunters Woods joining and running down Wineberry to the west.

This post presents maps to help find the path that the water takes from the roof of a particular house to the main stream of Northeast Creek and the features of the Northeast Creek wetlands that it passes through. Future posts will look at what you can do on your own property to help preserve effective functioning of Northeast Creek.

The following map is an overview of the Northeast Creek main stream from Carpenter-Fletcher Road downstream to the American Tobacco Trail bridge over Northeast Creek on the trail a half mile south of the Scott King Road trailhead.

The red line is the watershed ridge on the west between the Northeast Creek basin and the Crooked Creek basin.

From left to right the sub-basins of Northeast Creek are:

- A fork that arises in the Southhampton neighborhood and the edge of C. M. Herndon Park on Scott King Road;

- Tributary D;

- Tributary C;

- A tributary that runs from the Legacy at Meridian;

- A tributary that runs out of the Auburn neighborhood;

- A tributary that crosses Woodcroft Parkway east of Barbee Road;

- A tributary that flows into Meridian Park;

- The North Prong of Northeast Creek, the major tributary that flows down the west side of NC 55 and through Meridian Park;

- The main stream (Northeast Prong) of Northeast Creek;

- Buck Branch, which flow out of the old EPA campus area;

- The north fork, main stream, and south fork of Burdens Creek, which drains the central section of Research Triangle Park;

- Long Branch of Kit’s (Kitt’s) Creek;

- Another branch of Kit’s Creek, which drains the southern section of Research Triangle Park.

- Main stream of Northeast Creek.

This series of maps will show the western side (Parkwood side) of the main stream, that wide, blue and blue-and-red floodway that:

- starts at the top right of the map,

- flows south,

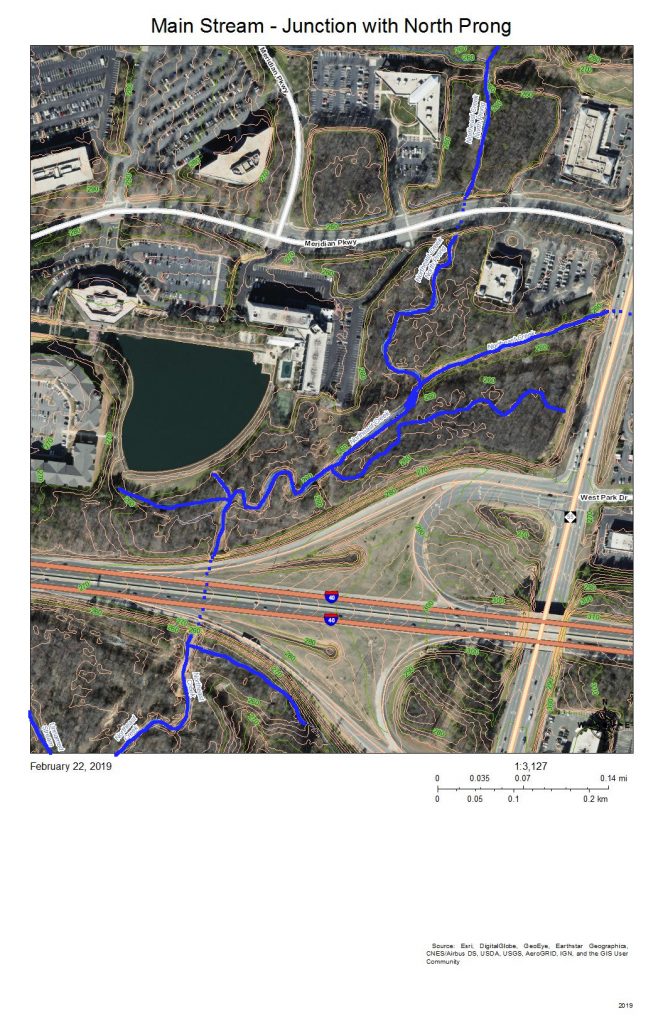

- then west again in passing the Red Roof Inn on NC 55 north of I-40 and connecting with the North Prong in the southeast corner of Meridian Park,

- then south again at the Doubletree Inn;

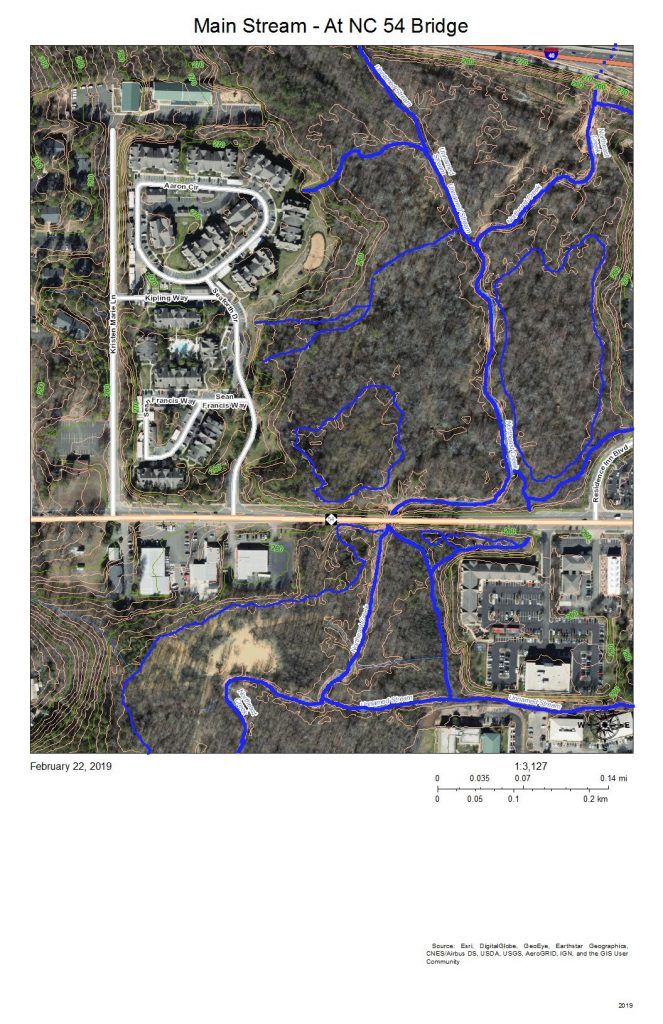

- then it crosses under I-40 and flows through a wetland between Parkwood and NC 55;

- Burdens Creek joins it from the east and Research Triangle Park;

- then turns west flowing south of Audubon Park and Parkwood, through Corps of Engineers unforested land and a Duke Energy high-voltage line easement;

- then it crosses under Grandale Road passing through forested Corps of Engineers land (NC Gameland);

- it crosses into Chatham County;

- Kit’s Creek joins it from the southeast and the southern part of Research Triangle Park;

- it flows under the bridge for the American Tobacco Trail, a bicycle and pedestrian trail.

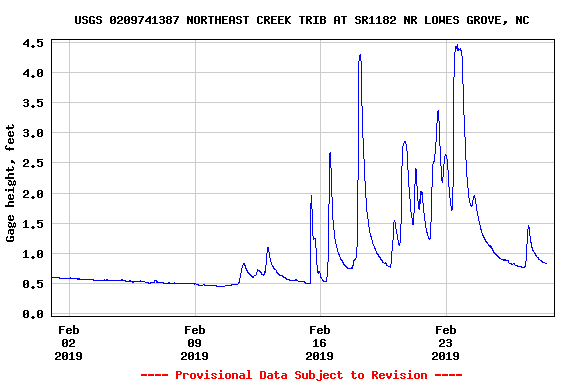

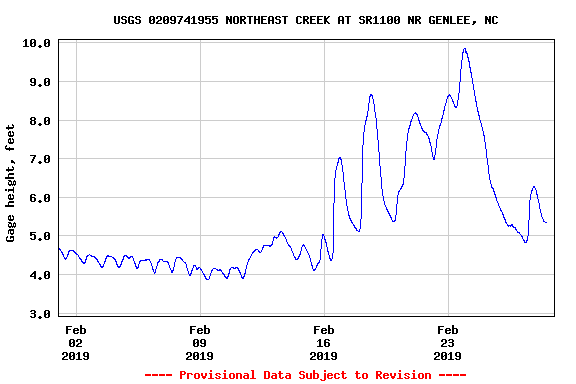

There are two stream gages placed by the US Geological Service on this section of Northeast Creek, one at Carpenter-Fletcher Road and the other at the bridge on Grandale Road. To provide a view of what this section of the main stream does, here is the February 2019 stream gage data for the Carpenter-Fletcher Road gage. Notice that the level during moderate periods is around 0.5 feet (6 inches), but rain quickly causes the level to rise to 2, the 2.5, then 4.5 feet. Remember these numbers when we come to the data from Grandale Bridge.

That stream gage is just upstream (north) on the North Prong (out of view off the top of this map).

The North Prong drains the Northeast Creek watershed south of Riddle Road and southwest of the intersection of Riddle Road and Alston Avenue. When it enters Meridian Park it flows into a wetland between NC 55 and Meridian Parkway (top right on the map).

I-40 appears at the top right of this map. The dotted blue line on I-40 is roughly where the culvert for Northeast Creek goes under I-40 and spills into the flood plain to the south. At the left end of NC 54 on the map is Christus Victor Lutheran Church; at the right end is Chik-Fil-A. The bridge is where the wetlands on the north side of NC 54 spill through to the south side of NC 54. This area regularly has high water during rainy spells.

Almost all of this wetland area except for the various stream channels is a wide intermittent flooded area during rainy spells. Drier weather allows for plant succession until water collects so frequently in those areas that it drowns out vegetation or gets replaced with water plants.

The drainage of the sub-basin north of NC 54 gets directed parallel and south of I-40 and flows into the wetlands south of I-40 and north of NC 54 (in the previous map). The sub-basin on the top right has a stream that flows from the intersection of Blanchard Road and NC 54 southeast into the engineered pond behind the commercial buildings on NC 54. The third sub-basin flows out of the pond at the Revere Road end of Euclid Drive, between the houses on Lattimore Lane and Euclid Road, under Euclid Drive at the bottom of the hill, and down a restored stream that replaced a culvert and into the main stream of Northeast Creek in the wetlands.

The sub-basin at the top shows the drainage into the creek that flows from the pond at the Revere Road end of Euclid Drive and the creek that crosses Euclid Drive along the road to the former package sewer plant location (when Parkwood contracted its own private water and sewer service). The sub-basin at the bottom left is the area on Brentwood Road that flows into Tributary C. The remaining sub-basin is the intermittent stream that drains Emerald Circle.

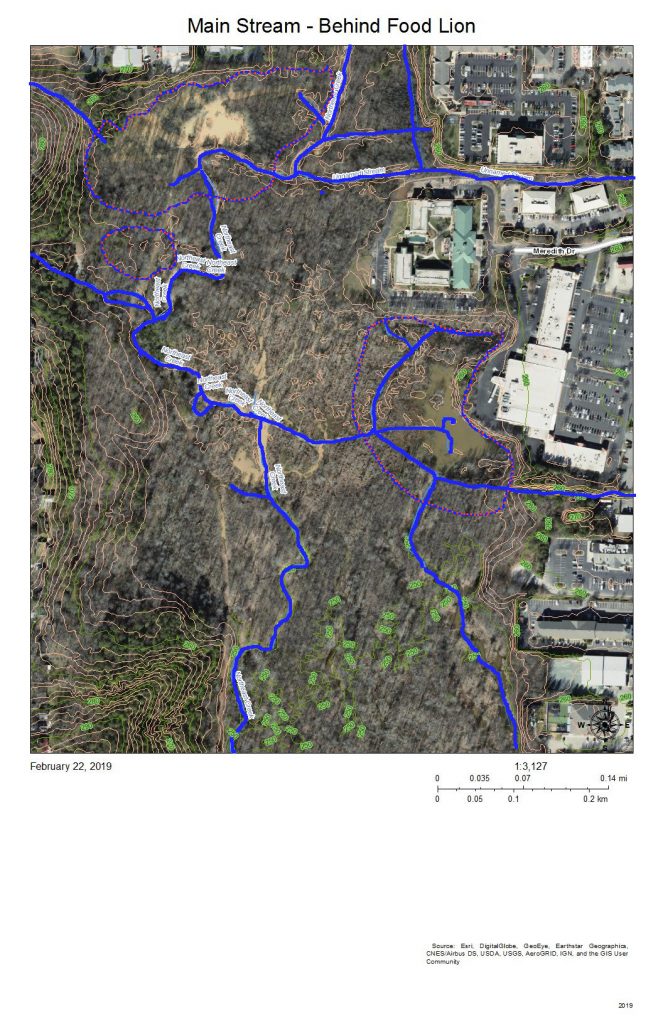

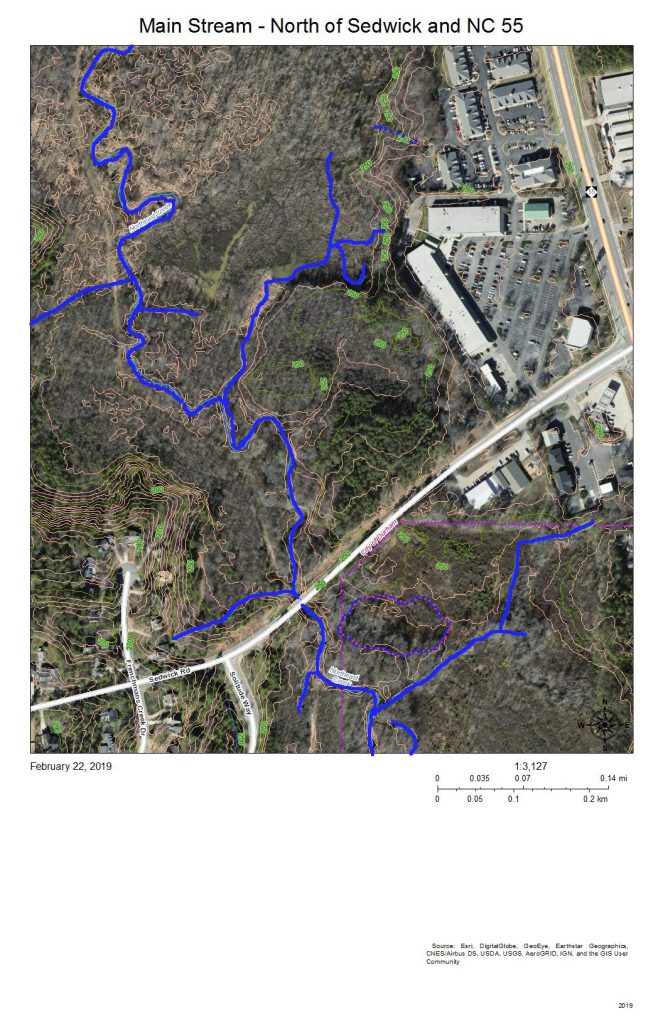

The complex pattern of blue lines (stream channels) on this map shows the effects of a strongly meandering and braiding Northeast Creek and the engineered attempts to reduce flooding of the parking lots of the properties backing up on the wetlands. All of the water from the parking lots built on what used to be farmland adjacent to bottom land instead of somewhat soaking into pasture or woodlands, now all flows into the wetlands. Commercial property owners nationwide are only now beginning to investigate how to better manage stormwater on commercial properties. Local governments have mandated certain best management practices for stormwater management over the last ten to twenty years. The most obvious of these to most customers are the retention ponds on the edge of commercial developments.

The blue and orange dotted lines encircle areas of open water in the areas behind the commercial properties on NC 54 and the Food Lion shopping center on NC 55.

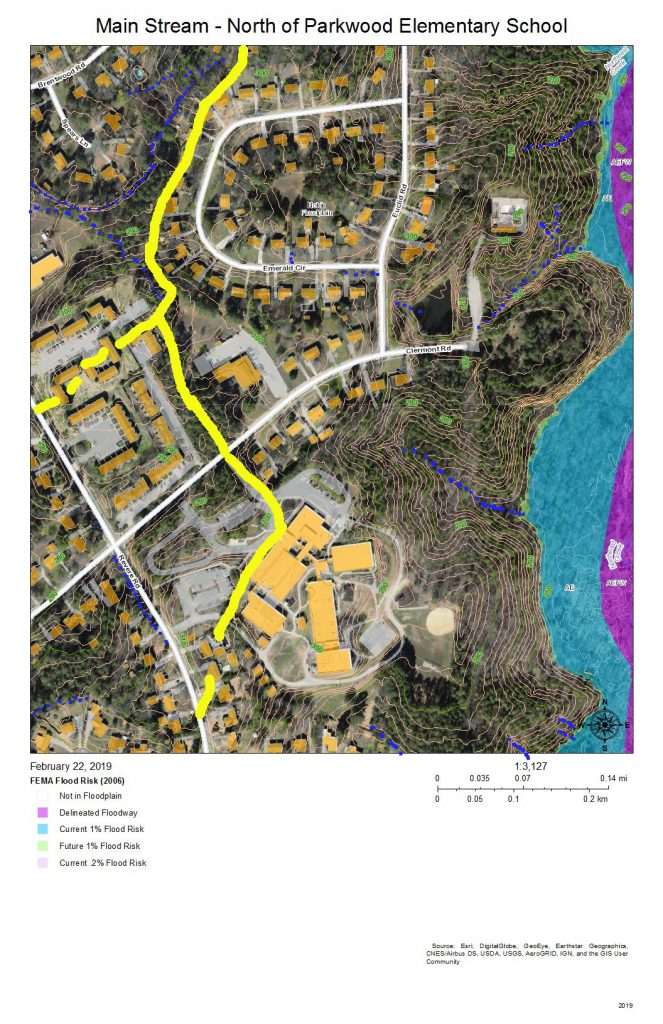

The sub-basins to the left of the map drain into Tributary C (Parkwood Lake). Parkwood Elementary School has engineered stormwater management of its site. The houses on Radcliff Circle drain down the vegetated ground cover of the buried sewer outfall to the main sewer line that goes to Triangle Wastewater Treatment Plant on NC 55.

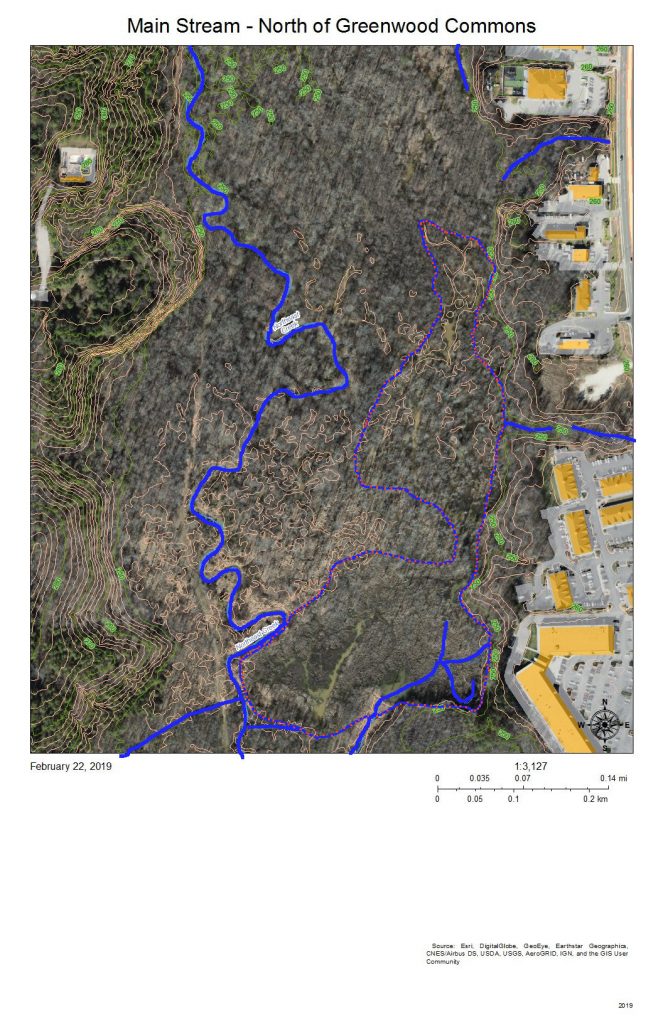

As the intensity of commercial development on the eastern edge of the wetlands diminishes and as the force of flooding during rainstorms is absorbed by the size of the bottomlands, there are fewer engineered channels and the channels go from braided to parallel meanders. The blue lines show stream channels; the blue and orange dotted lines show the perimeter of the more permanent swampy and marshy areas toward the eastern edge.

At the bottom of the map behind Greenwood Commons, the eastern side is a cattail marsh with a few snags. This marsh has been flooded by a natural dam of crushed branches and cattail stems that elevates the water impounded slightly above the western branch, which has a series of meanders. The two branches join shortly before the main stream passes under the bridge on Sedwick Road.

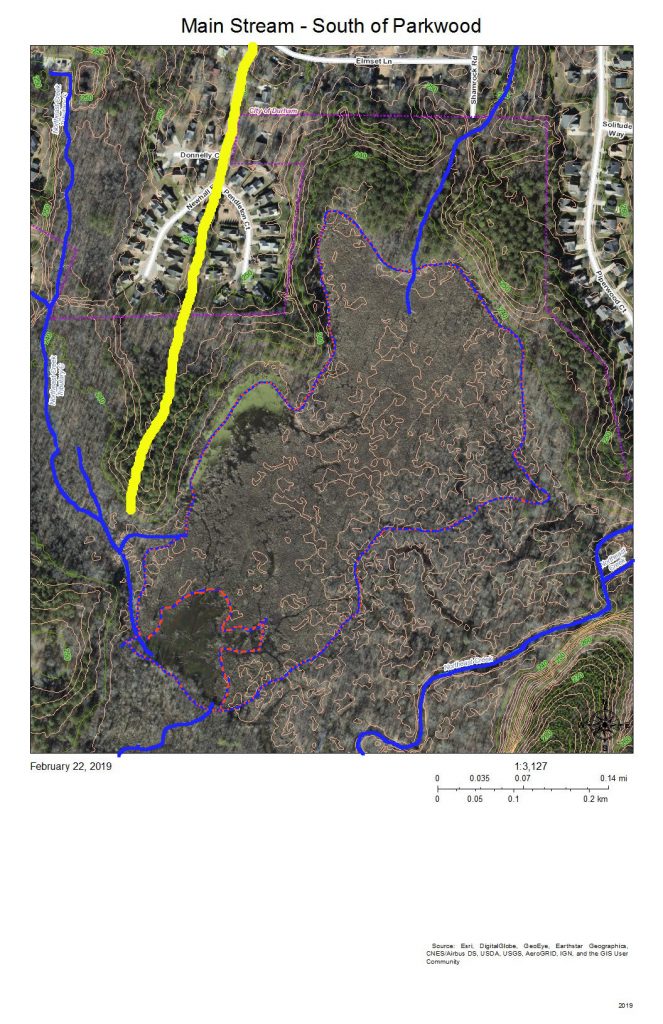

The primary drainage between the heights at the Parkwood Elementary School building and the short ridge on which Frenchman’s Creek Drive is built is the grassed sewer line easement (solid blue line) that runs from Radcliff Circle back to the main sewer outfall easement in the wetlands; both of these easement are somewhat wet from unevaporated stormwater except in very dry periods because of the intermittent streams (dotted blue lines) and groundwater flows that allow what rainwater that does soak in to be delayed in adding to the stream flow.

Water runs off the impervious surfaces, such as roofs (orange), driveways (gray), and streets (white). The runoff that comes through the dark green forested area that have a lot of leaf litter moves much slower. The water that does percolate through into groundwater move slower still.

The simple rules for managing rainwater on your own property are:

- Slow it down.

- Spread it out.

- Soak it in.

This area shows how the undisturbed common land buffer on the steeper upland slopes between the individual house property and the wetlands carries out those functions.

The blue lines show:

- To the west, the meandering stream channels of the west branch of the main stream of Northeast Creek running just east of the sewer line easement that runs to the Triangle Wastewater Treatment Plant.

- Coming in from the southwest, the tributary stream that has formed from the accumulated groundwater and runoff flowing from the heights of Parkwood Elementary School, Radcliff Circle, and Frenchman’s Creek Drive.

- From the marsh behind Greenwood Commons, the stream channel that has flowed nearest the commercial properties on NC 55.

- The joining of the two meandering channels into the single Northeast Creek main stream

- A tributary paralleling Sedwick Road and draining that part of Frenchman’s Creek Drive

- The single channel of the main stream of Northeast Creek flowing under the Sedwick Road bridge.

- Burdens Creek and its wetlands joining Northeast Creek from the east.

- A north-flowing creek to the east of Solitude Way.

- An oxbow lake just southeast of the junction of Burdens Creek and Northeast Creek.

The blue and orange dotted line encircles an area that became a intermittent pond after the property was logged. The property is going through succession of vegetation and now is beginning to have small trees and forest sub-story beginning to grow. Several years ago there was a cattail marsh in this wet spot.

You can also see some of the unmarked meanders, tributaries, and oxbow lakes as darker areas near the streams.

Audubon Park was developed with intensive site preparation and most likely stormwater pipes and structures to conduct runoff quickly into the wetlands to the east and south. What appears on this map is a stream inside Piperwood Circle and Solitude Way. There are also indications from the topography that intermittent streams might form with the slope of the ground and run off at the edges of the wetlands; after almost 20 years, there might be gullying at the edge of the wetlands (near where the blue dotted lines meet the color coding of the flood zones). Homeowners in Audubon Park have the best view of how the water runs because so much of the drainage is enclosed interior to a bunch of houses and not visible by the public.

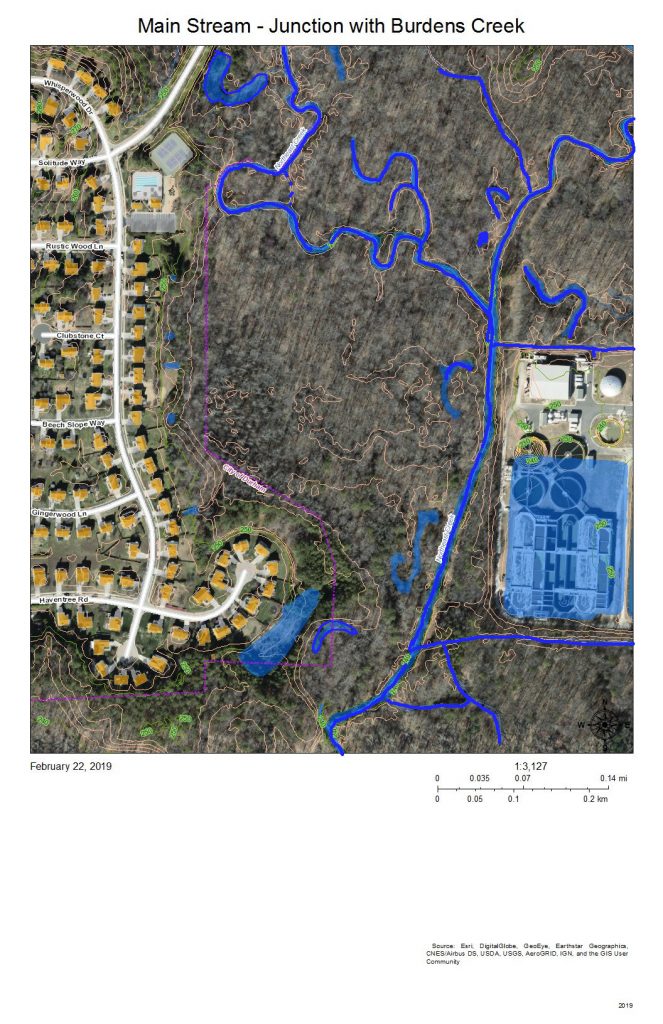

The wetlands east of Audubon Park show the meanders and oxbow lakes of intermittent flooding of bottomland forest in the area where Burdens Creek, coming in from the northeast, meets the main stream of Northeast Creek, meandering in from the north and making a eastward turn. The Triangle Wastewater Treatment Plant is at the lower right.

The processed wastewater coming out of the Triangle Wastewater Treatment Plant tests cleaner than the water in Northeast Creek at the outlet point. Also, the volume of wastewater flowing through the Triangle Wastewater Treatment Plant cause a baseline oscillation of roughly 6 inches (0.5 feet) in the USGS stream gage at the bridge on Grandale Road of a typical dry-period stream height of 3.5 feet. (Notice this on the stream gage report at the end of this post.)

The main stream turns to the west around the southeast corner of Audubon Park. On the map, the development at top right is the back edge of the Triangle Wastewater Treatment Plant. The blue lines are the meanders and loops of the main stream of Northeast Creek and the tributary streams that drain other parts of the wetland.

The area on the left marked with a blue and orange dotted line locates a former swamp forest, now characterized by snags and fallen trees killed by the persistent deeper water.

The two lines across the bottom are the high-voltage power line running from a substation on NC 55 to a substation on Scott King Road by the American Tobacco Trail.

This section is where Corps of Engineers ownership of the headwaters of Jordan Lake begins on Northeast Creek.

This view is slightly to the west of the previous view; the area of snags and fallen trees noted at the left of the previous view is in the center of this view. To the left of this view is another swamp forest in decline.

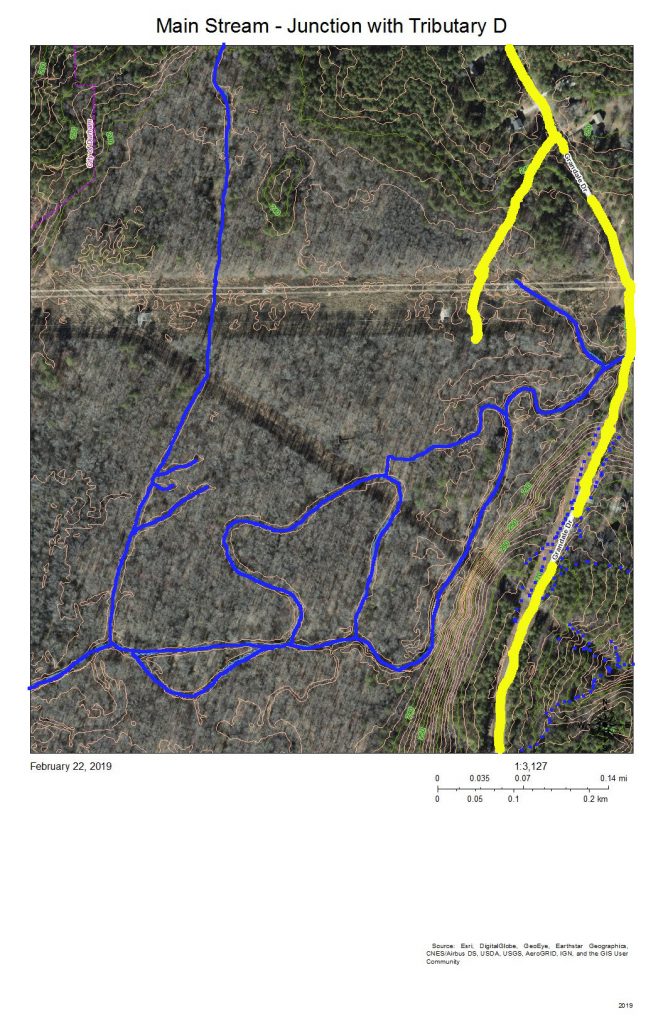

The yellow line is the headwaters ridge between the main stream of Northeast Creek and Tributary C of Northeast Creek.

The solid blue lines are the more permanent streams, and the dotted blue lines are the intermittent streams that drain the streets off Newhall Extension in Parkwood.

At the end of Shamrock Road is a triangular-shaped upland buffer of common land that faces out on a large freshwater marsh interrupted by some of the areas of flooded snags and fallen trees. Notice that the buffers between the newer developments and the wetlands are much narrower.

This is the same as the previous view but without the color coding for flood hazard areas. The yellow line is the watershed ridge between the sub-basin of the main stream and the sub-basin of Tributary C of Northeast Creek. The areas enclosed in blue and orange dotted lines are areas that are more permanently wet, such as snag areas, freshwater marshes, and open ponds. There is an area in the water at the end of Pendleton Court that is light green; this appears to be algae bloom. Beyond it is a dark area of open water, and then the speckled area of the freshwater marsh. Toward the bottom left is a dark open water area, enclosed with a blue and orange dashed line, in which fallen trees are clearly visible. Within the marsh are thin, short slashed lines that are the shadows of standing trees. The open water through the marsh shows meanders that might show areas of faster flow.

On the bottom right is a 40-foot hill that forms a bluff at the southern edge of Northeast Creek.

All of the ricocheting of water in this wetland slows it down and allows it to spread across the low areas and soak in as best it can in the Triassic and floodplain soils.

The Grandale Road bridge is just south of where the high-voltage power lines cross Grandale Road.

The yellow lines mark the headwater ridges that separate the sub-basins of, from east to west: the main stream, Tributary C, and Tributary D of Northeast Creek.

The features of the wetland north of the power lines are those we have discussed above. This view shows more of the wetlands to the west and south.

The 40-foot hill turns out to be a 60-foot ridge that edges the floodplain on the south. Almost all of the bottom land in this view is Corps of Engineers property marked as NC Gamelands.

The USGS gage station is on the bridge. The following is the report from the month of February 2019.

Notice the daily cycle for the first eleven days of February. That is the record of the daily release of the TWWP, just that between roughly 5.0 inches and 4.5 inches. Increased streamflow begins around February 12 and rises through multiple peaks to almost 10 feet before decreasing toward the end of the month, with one rainfall around February 28.

Compare this pattern with the pattern upstream from the stream gage at Carpenter-Fletcher Road.

The yellow lines separate Tributary C on the east, Tributary D on the west, and a short minor tributary of the main stream in the middle. The meanders and islands are the pattern that the main stream takes through this section in which it is receiving the flow from Tributary D, the long, more-or-less straight, stream on the left.

The diagonal line is a natural gas pipeline easement.

The green line at the bottom right is the Rails-to-Trails American Tobacco Trail (ATT) that runs from the Durham Bulls Athletic Park to the village of New Hill in Wake County. The gap is just to allow the bridge over the Northeast Creek to be visible.

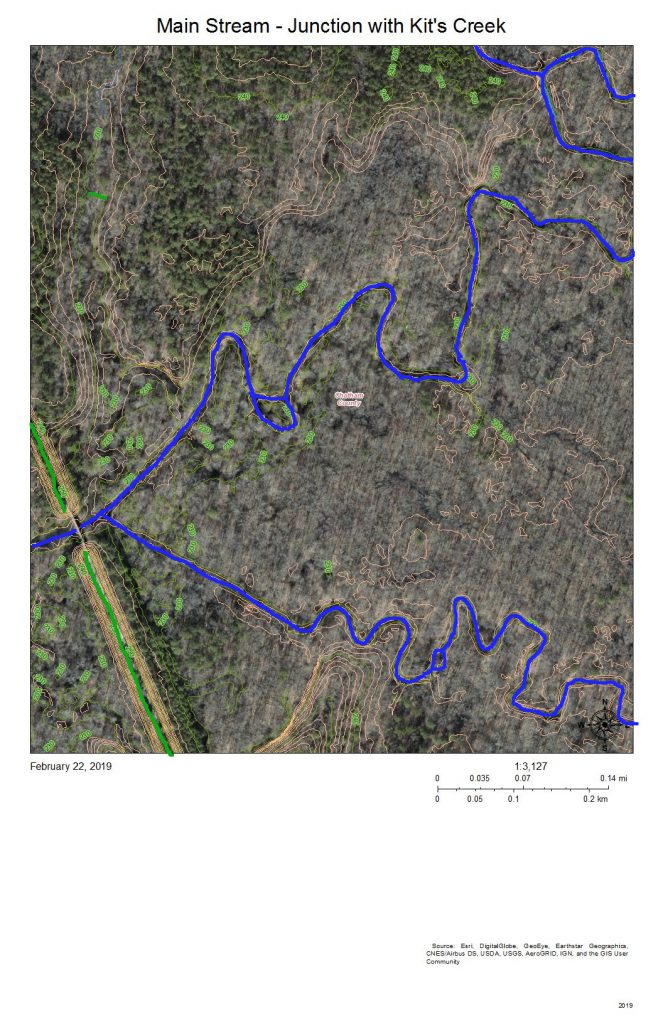

Kit’s Creek (Kitt’s Creek is also correct) flows from the southeast and joins the main stream of Northeast Creek right before the ATT bridge. This junction is in Chatham County.

The area to the north of Northeast Creek is bottom land hardwood forest that includes some magnificent beech trees and shagbark hickories.

This entire floodplain down to the rookery at the mouth by the NC 751 bridge is owned by the Corps of Engineers and administered by the NC Wildlife Commission as gameland.

Another fun activity is to see where your water goes when it leaves the Parkwood area. A great way to explore this part of Northeast Creek is to hike or bike on the ATT; an alternative is to park at the parking lot by the NC 751 bridge, put in your kayak in the bay to the east and paddle upstream as far as you can (generally short of Panther Creek because of beaverdams and blowdowns).